January 10, 2018

by Brett Morris, Principal for TechAccel

Early in 2017 I was approached by several CEOs seeking additional funding for their startup. This is nothing out of the ordinary for venture professionals as we see hundreds of deals come across our desk annually. These conversations, however, were different from the previous year. Most of the entrepreneurs were struggling to find investors with an appetite for early-stage risk. They secured initial seed funds, but needed additional runway to prepare for a more valuable Series A financing. Some of the companies had even achieved significant milestones and were actively raising a Series A round.

I began wondering whether an important trend was emerging in the agtech ecosystem. These companies appeared to be trapped in the early-stage funding gap – between the accelerators/incubators of the world and the investors that typically wait to invest in proven technologies with growing sales and established distribution channels.

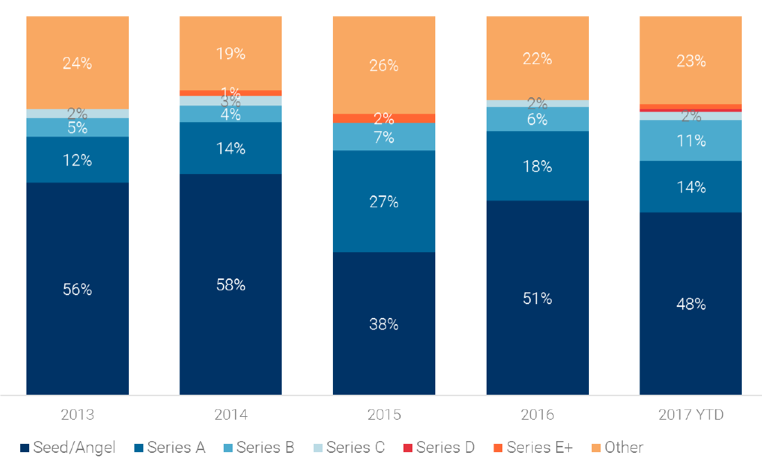

As I dug into the data, I noticed agtech angel/seed funding was on the rise over the last couple of years, while Series A funding showed a sharp decrease in 2016 from the previous year. More startups competing for a limited amount of funding at the next stage presents a problem for many founders.

I believe the industry is long overdue for new investment models that can bridge early-stage funding gaps and prove the sustainability of the agtech venture ecosystem. The first step in closing the gaps, however, is to understand what might be causing them.

What’s Causing the Funding Gap?

For starters, technology has drastically lowered the barriers to entry for startups across sectors, allowing entrepreneurs to turn ideas into products much faster. This is especially true in ag-biotech, where a range of once-daunting capital requirements have plummeted in cost. The cost of genome sequencing has declined from $100 million per genome in 2001 to approximately $1,000 per genome in 2015, faster than predicted by Moore’s Law. Cheap cloud storage now allows companies to host, analyze, and reproduce huge data sets. Computing power has significantly increased and enabled advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning. As a result, companies are observing phenotypic characteristics in the lab versus the field, and continuously improving outcomes by feeding more data to smarter algorithms. And the insights these startups are producing are moving into development faster thanks to high-throughput automation. In simple terms, this means it’s easier to start a company today than ever before.

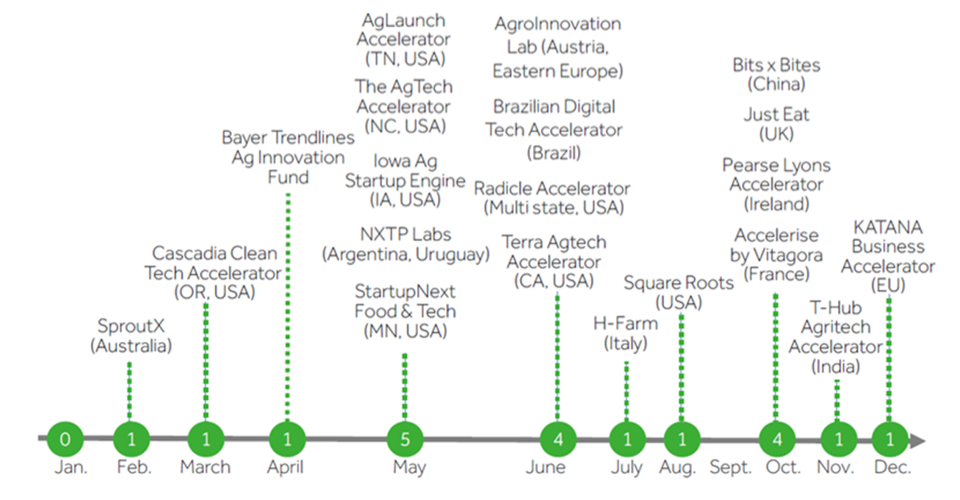

As technology has accelerated the business cycle, we’ve seen an equal surge in tech accelerator and incubator activity. In 2016, 16 new incubators and accelerators launched in food and ag, bringing the industry total to 77.

Source: AgFunder Annual Report, 2016

Accelerators are great programs, but typically do not provide much capital support – on average $50,000 for a 4-9 percent equity stake. Many have good intentions and try to replicate the larger successful programs like TechStars, Y Combinator, and The Yield Lab, but lack the same leadership, networks, and follow-on funding capacity, leaving companies stranded after initial funding and launch. Federal grants also add to the flood in new startup activity and can represent excellent sources of non-dilutive capital if utilized correctly. However, we’ve seen several cases where grants lack commercial supervision and end up being a major distraction to the company instead of a tool to achieve milestones and secure future funding.

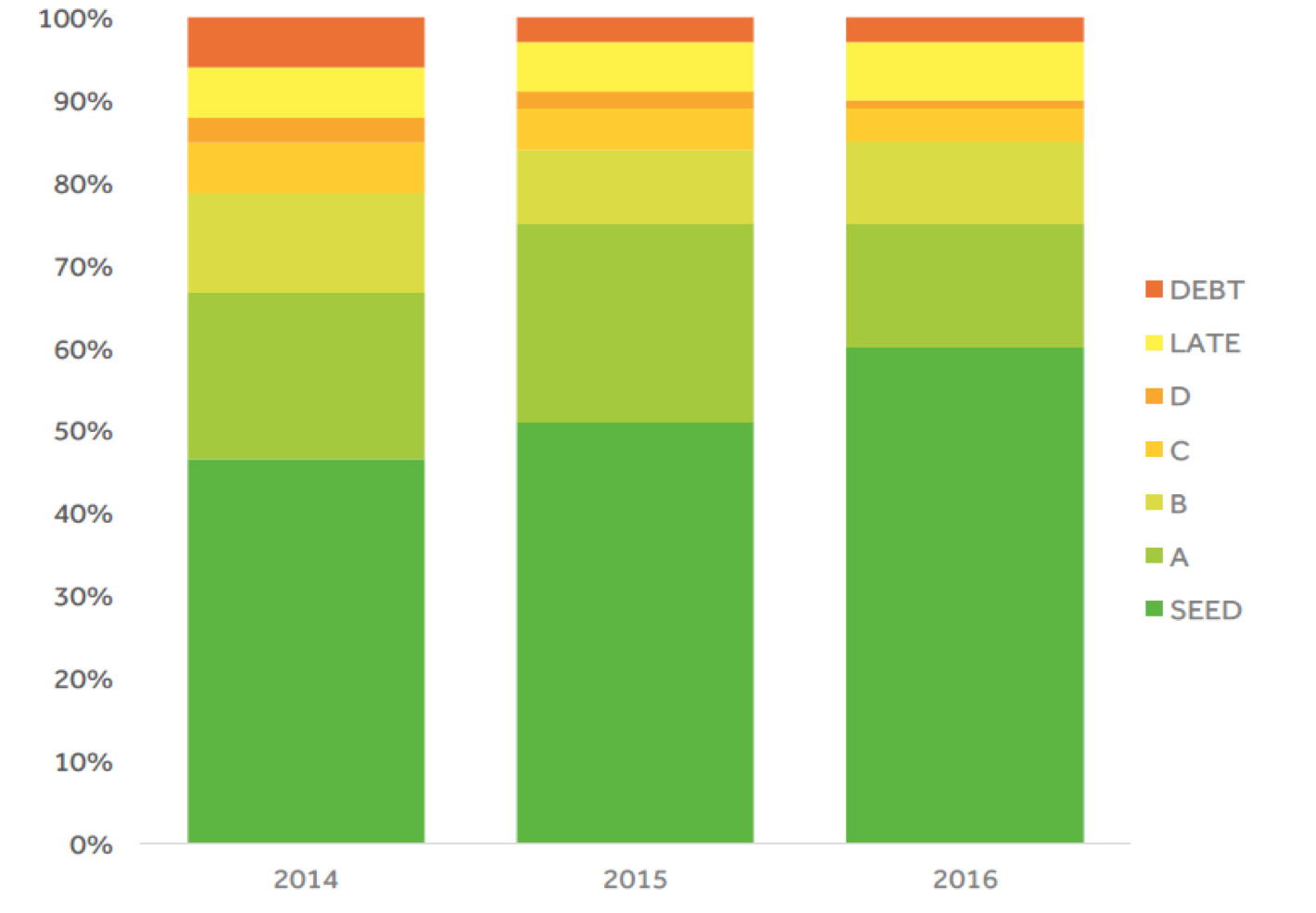

According to AgFunder’s 2016 annual report, seed stage deal share (as a percentage of total deals) steadily increased over the three-year period from 2014 – 2016, growing from $120 million in 2015 to $230 million in 2016. In contrast, Series A deal share declined by 42 percent in 2016 to $469 million versus $786 million in 2015, while the number of deals decreased by 30 percent to 86 from 123.

CB Insights data reveals a similar pattern, with Series A deal share declining from a high in 2015.

Source: AgFunder Annual Report, 2016

AgTech Global Deal Share 2013-2017 YTD (11/2/17)

Source: CB Insights “Cultivating ag tech” report, Nov 2017

While accelerators and federal funds continue to churn out more startups, there is a notable shortage of dedicated agtech investors deploying capital at the later seed and Series A stage, especially in biotechnology. This creates a funding gap as more startups compete for a finite amount of resources. According to AgFunder, by the end of 2016, there were approximately 15 active agtech funds worth more than $900 million compared to the $3.2 billion invested across the space.

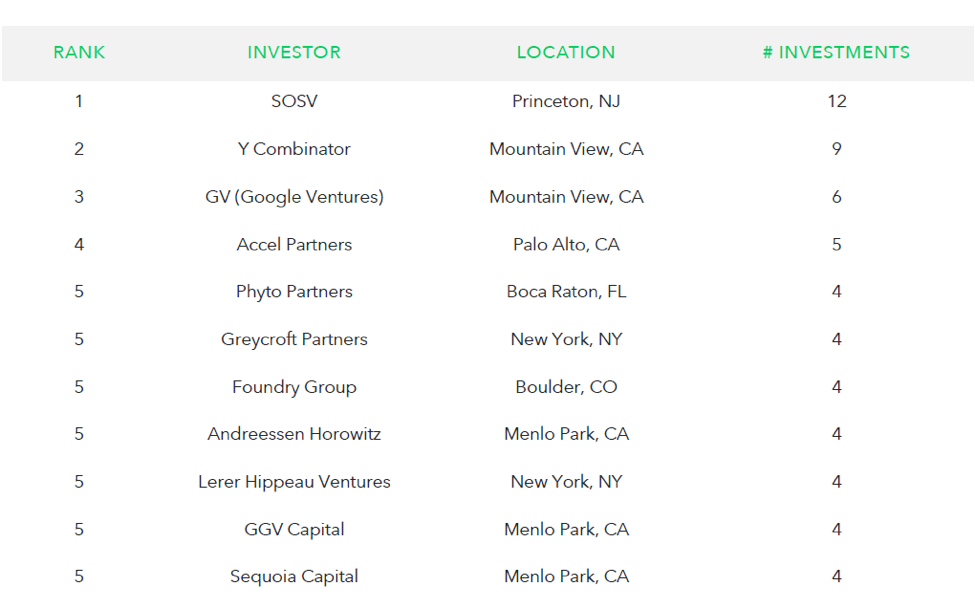

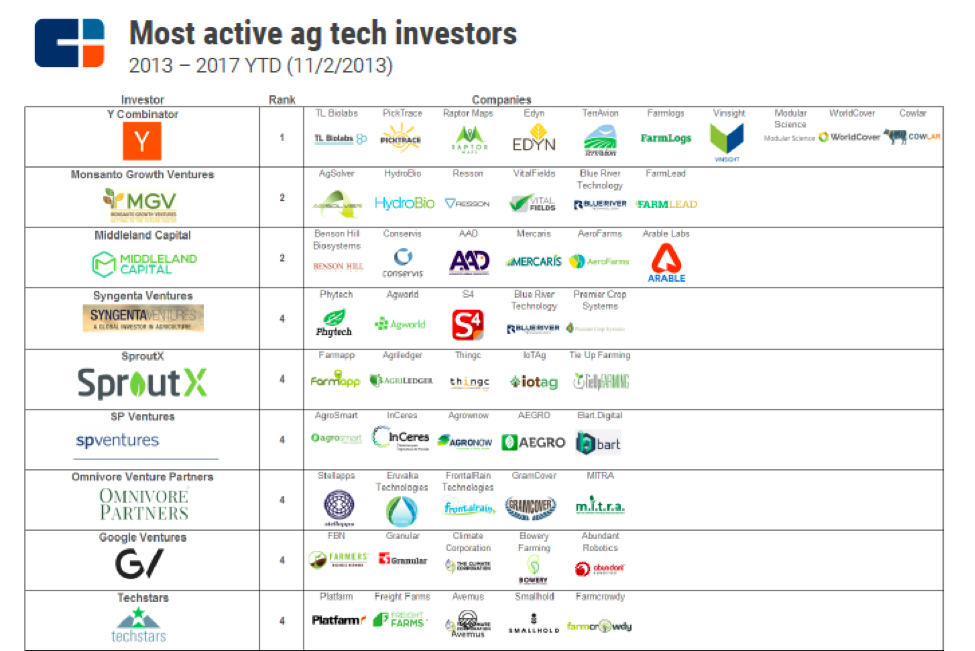

Agtech is still dependent on non-ag focused investors like family offices and big-name Silicon Valley VCs: In 2016, Google Ventures made five investments across the sector, all at the Series B round or later, while Khosla Ventures and Kleiner Perkins Caufield and Byers made three each. CB Insights notes that we are starting to see more investment from agtech dedicated funds; however, large generalist firms like Greycroft Partners, Andreessen Horowitz, and again, Google Ventures were the most active in agtech through the first half of 2017.

Most Active AgTech Venture Funds

Source: AgFunder Mid-Year Review, 2017

Source: CB Insights “Cultivating ag tech” report, Nov 2017

Agriculture is also a niche industry, requiring a deep understanding of science, technology, and a well-established market and end customer. This becomes even more apparent with ag-biotech companies, where disciplines such as genomics, biochemistry, and molecular biology are highly important. Generalist investors and individuals tend to shy away from early-stage risk if they don’t understand the industry or underlying science.

Venture firms investing at later stages appear to be doing so for good reason. According to DunRobin Ventures Partners, only 2.4 percent of seed stage companies, 17 percent of Series A companies, 56 percent of Series B companies, and 85 percent of Series C stage companies ultimately reach profitability. This does not capture the full story, however, as more risk at earlier stages is compensated by significantly greater returns. When considering lifetime return statistics (adjusted for changes in pre-money and post-money valuations) and lifetime failure data, DunRobin found the greatest expected risk-adjusted returns were achieved at the Series A and Series B stages. This is interesting and worth noting given the recent downward trend in Series A financings.

Closing the Gap

So how do we solve the funding gap? Partly, the answer lies in raising more dedicated funds for the sector. Today, the industry is still immature and highly collaborative, which is great for investors. There are more opportunities than available capital, which increases the chance to earn impressive returns.

While more capital is one solution, rethinking the structure and strategic value of funding models to reduce early-stage risk is another. Here are three innovative approaches for de-risking early stage agtech plays and closing the funding gap.

- Provide Patient Capital

The GP/LP structure of a venture firm implies a typical timeline, at the end of which investors expect a strong return. But in an industry that often has to develop a proof of concept in the soil, an industry in which the science isn’t always on a predictable timeline, the typical funding model isn’t optimal. Evergreen funds, such as Prelude Ventures, have the flexibility to continuously move capital into their portfolios without strict open and close dates. This allows investors to focus on building value in their portfolio companies versus feeling pressured to exit early. Selling too soon can (at times) have a negative impact on a company’s prospects and reduce the overall return on investment for shareholders. Patient capital also provides increased flexibility to adapt to changing market conditions. For example, the long-term vision for a startup may be to pursue the public markets in an IPO; however, industry fundamentals may shift over time causing the management team to re-think its strategy. Funds sticking to a pre-determined timeline may need to sell their shares quickly to satisfy LP liquidity needs. This is one of several reasons why TechAccel is structured as an operating company.

- Fill the Knowledge Gaps

If generalist funds are hesitant to back a play because they don’t understand the science behind it, then companies that can perform financial and scientific due diligence have an advantage. Corporate venture models, such as Monsanto Growth Ventures and Syngenta Ventures, can efficiently de-risk opportunities because they have large R&D departments and scientists to help with diligence. They also have large-scale plots of land to perform high-powered statistical proof-of-concept studies to validate technologies. And by providing exit opportunities and ongoing business relationships with the startups in which they invest, these corporate ventures are able to further reduce risk.

But big corporate venture funds aren’t the only players who can fill these knowledge gaps. While focused on growth equity rather than early stage funding, Pontifax AgTech has several corporate partnerships with entities like The Wonderful Company, one of largest vertically integrated producers of permanent crops in the world, which allows for direct feedback and on-farm testing of technologies. This partnership model is something more Series A investors should copy. Fall Line Capital, meanwhile, has taken the unique step of investing in both farmland and innovative agtech, allowing it to use its own plots to test and validate technologies before it invests. Other ways funds can reduce risk is by leveraging the knowledge and strengths of their LPs or by hiring experts in-house that have business/financial acumen and scientific expertise, what we refer to as “dual due-diligence capabilities.” Firms like Cultivian Sandbox, Middleland Capital, Lewis & Clark, and TechAccel have a unique mix of technical and business professionals on their staff.

- Integrate the Whole Value Chain

While filling knowledge gaps is critical, building strong relationships with each player on the path to commercialization is just as important. TechAccel vertically integrates itself from the lab to the marketplace by partnering with universities, startups, corporates, and end customers. We reduce risk by learning and influencing at each stage of the commercialization value chain.

Through deep relationships with top universities and research institutions, TechAccel can quickly test and validate technologies. These connections also keep us ahead of market-disrupting trends by supplying direct access to the most innovative discoveries, and provide a pool of best-in-class experts to augment our due diligence process. For example, our collaboration with, and office inside the Danforth Plant Science Center allow us to create weekly interactions with top researchers that are developing some of the best plant science in the world.

In addition to research connections, TechAccel invests in startups. Beyond an equity investment, we bring additional capital and scientific resources to further develop and commercialize a company’s technology in new or adjacent markets. We look for platforms that can be leveraged and applied to a new crop, animal, or sector. Ultimately, the objective is to create more shots on goal for the company and maximize shareholder value without distracting management from executing on current milestones. This approach reduces risk for both parties. The startup can bring more innovation to market at a quicker pace which diversifies their internal portfolio. Meanwhile, we create a financial structure that allows the newly leveraged asset to remain valuable even if the startup falters.

TechAccel also partners with global strategic corporations to help fund and de-risk technologies that are stranded on the shelves and have slipped below prioritized funding. We regularly meet with corporate partners to understand their market needs and assess areas where technologies could expand existing product portfolios and improve the bottom line. By having these established relationships, agtech funds can gain insights into market opportunities, industry trends, and distribution channels. This helps investors identify unmet needs, fill gaps in major corporate R&D pipelines, and secure exits for portfolio companies.

Finally, in the midst of trying to understand what researchers, entrepreneurs, and big corporates say is possible, it is all too easy to lose sight of the end customer, the farmer. Investors must form a robust network of growers as they will ultimately decide whether funding strategies have helped the right products reach the market.

Conclusion

Only time will tell whether the trends in seed and Series A funding continue. A recent report in TechCrunch highlights a significant decline in seed and Series A funding over the last three years across all sectors and geographies.

The answer, however, is not less startups. Innovation is a driving force in the economy and needed in an agriculture industry laced with M&A consolidation and decreasing R&D budgets. The agtech ecosystem needs more dedicated capital and new investment models that will reduce early-stage risk, support entrepreneurs, and fund the next wave of innovation.

~ The details in this article are designed to provide helpful information on the topic(s) discussed. All views, data, opinions and declarations expressed are solely those of the author(s) and not of GAI News or its parent company HighQuest Group.

Let GAI News inform your engagement in the agriculture sector.

GAI News provides crucial and timely news and insight to help you stay ahead of critical agricultural trends through free delivery of two weekly newsletters, Ag Investing Weekly and AgTech Intel.