January 9, 2020

By Gerelyn Terzo, WIA Media*

The state of California is no stranger to calamity, as evidenced by the persistent droughts and devastating wildfires that have ravished the land in years past. Now, however, it is facing a crisis of another kind, and at this critical juncture the fate of the global agriculture industry hangs in the balance.

California comprises 14 percent of the U.S. economy, much of which is fueled by agriculture. The state’s agriculture industry produced $50 billion in output last year. California supplies approximately 50 percent of the country’s fruits, nuts, and vegetables across almonds, apricots, avocados and many more grown foods.

However, a law crafted in 2014 dubbed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), a product of the severe seven-year drought, stands to jeopardize ag production in the state, which has far reaching implications nationally and around the world.

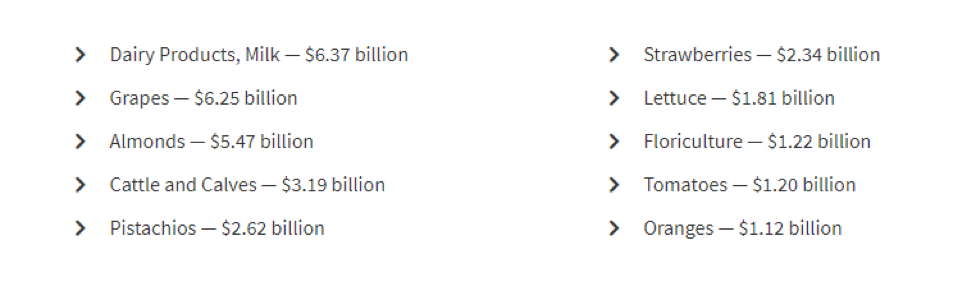

Table: California Leading Commodities in 2018

Source: California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA)

While SGMA is designed to ensure that California’s water basins are sustainable, it is also backing farmers into a corner. That’s because it slashes the amount of groundwater they are allowed to pump, which cuts into the lifeblood of farmers. Worse, there isn’t enough surface water access to offset the damage, leaving farmers in a Catch-22.

California’s massive water infrastructure comprised of dams, reservoirs, canals, and two of the world’s largest water projects — the State Water Project and Central Valley Project — is rivaled only by demand for the finite resource. And while California experiences hundreds of millions of acre-feet of rain annually on average, there isn’t enough water for all.

Some of it has to do with California’s unique geography, with the lion’s share of precipitation falling in the northern part of the state and more than half of the rain being directed toward evaporation or transpiration. But much of it has to do with distribution and access, or lack thereof. With supply spread thin, a battle has been raging between environmental extremists and the farming community, and it’s coming to a head.

Kristi Diener, founder of the California Water for Food and People Movement, resides in California’s Central Valley. She explained how we got to this point, which comes down to a drop in the amount of water that’s pumped from the State Water Project and Central Valley Project as a result of policies.

“Almost all the water behind the northern reservoirs must pass through the Delta first. When water flows through the Delta, it either continues out to the ocean or is pumped, captured, conveyed, and delivered to the lower two-thirds of the state,” said Diener. “There is too much water going out to sea.”

The groundwater pumping restrictions can be traced back to efforts to save endangered species such as the Delta Smelt and Chinook Salmon. California’s water pumping restrictions are a one-two punch because not only are they damaging to farmers, they have not had the desired effect on threatened species over the last decade either.

“Pumps are ratcheted down at the same time as spring snowmelt, and at the same time excess water is emptied from reservoirs in the fall for flood protection from the upcoming winter. These failed policies have prevented us from capturing the surface water necessary to sustain agriculture south of the Delta, without turning to groundwater pumping. Twenty-eight-and-a-half million acre-feet of fresh water has gone to the Pacific Ocean from Oct. 1, 2018 to present,” explained Diener.

SGMA and Ventura County

With a Jan. 31, 2020 deadline looming for California counties with severely overdrafted groundwater basins to submit Groundwater Sustainability Plans to the Department of Water Resources, tensions have never been so high.

Ventura County is known for high-value crops ranging from lemons to avocados to berries to celery and various citrus fruits, all of which are grown across thousands of family farms. Some of these crops command more water than others.

Jeanette Lombardo, national president of American Agri-Women, chief strategy officer at Global Water Innovations, and past president for California Women for Agriculture, resides in Ventura County.

She explained that the county’s Groundwater Sustainability Plan has a hefty $79,302,272 price tag attached over the course of the next 20 years.

“There is not one penny of that money going for the production of new water sources,” said Lombardo, who also noted: “The pain, expense, and hostility of SGMA doesn’t affect the stakeholders equally. Agricultural owners and their employees will bear the brunt of this legislation.”

Ventura County comprises 10 percent of California’s medium-and high-priority groundwater basins. Some basins are bracing for 40 percent cuts in current groundwater usage over the next two decades, as the sustainability target is 2040 or so.

“The anticipated cuts in water allocations to growers is pretty brutal on the Oxnard Plains. It’s not as bad here as it’s going to be in the Central Valley, but it’s bad enough,” said Lombardo, adding: “Farmers are either going to have to grow a different crop or they are going to have to take a section of their land out of production.”

The fallout extends beyond farmers’ backyards. Lombardo explained that decreases in planted acreage will hit peripheral industries, from packaging to trucking companies, which won’t have the necessary volume to operate. This, in turn, will have a trickle-down effect that will hit land rents, sending property values plummeting.

“California will start to see the crumbling of the infrastructure that we need to get our crops from the field to your plate before they spoil,” said Lombardo, adding: “To me, a domestic food supply is a matter of national security and what is happening to California farmers will have repercussions across our nation,” noted Lombardo.

Indeed, farmers are between a rock and a hard place, having to decide between growing a different, often less-valuable crop and taking a section of their land out of production, a phenomenon which is already happening.

While farmers have 20 years for the full effect of SGMA to be realized, it’s akin to a ticking time bomb. Lombardo explained:

“The 20-year implementation period of SGMA does give people time to make business decisions such as conducting crop conversions, or developing an exit strategy by placing their families land up for sale. The question is who would buy it?”

That’s because of another policy known as SOAR, which stands for Save Our Agricultural Resources. While on the surface it appears designed to protect ag, it’s a double-edged sword because it basically prevents farmers from using their land for any other purpose than growing crops – at least not without a fight.

“The time has come to determine who will continue to be able to farm and who will not. I do not think the residents of Ventura County fully understand what they have done to themselves and their neighbors,” Lombardo said.

Central Valley and SGMA

California’s Central Valley is comprised of the San Joaquin Valley to the south and Sacramento Valley to the north. Hundreds of crops are grown there, and the valley produces much of the fruits and vegetables consumed in the country.

The Central Valley is also where Kristi Diener calls home, farmland that she describes as “the most valuable asset in America.” She points to the valley’s Mediterranean climate and class-one soils, which when combined with a 100 years of successful farming history, makes it second to none for ag.

“We are the most productive agricultural region on earth growing more than 400 food and fiber crops, and we do it using fewer resources than anywhere else on earth. But we need reliable water to do this,” said Diener.

SGMA isn’t making that easy.

“SGMA says we can’t take more water out of the ground than what we put into the ground. There are no plans to give us more surface water. Are farmers supposed to magically make groundwater sustainable without any increase in surface water deliveries? The results will be devastating,” exclaimed Diener.

She goes on to explain how California’s last drought idled 500,000 acres, adding: “With SGMA in a drought year, it will be closer to 1.5 million acres during drought.”

Put another way, SMGA is expected to result in 1 million acres of farmland a year being knocked out of production. And as she points out, it’s “the most fertile land on the planet”. One acre alone can produce enough food for 30 men, women, and children for a year. That’s 45 million people getting their food from other sources, which Lombardo and Diener agree creates a food security issue.

Hudson Farms

Hudson Farms is a fifth- and sixth-generation family farm located in Del Rey, Calif., and run by Liz and Earl Hudson. They grow fresh market tree fruit and process peaches for the frozen market. Liz tells Women in Agribusiness (WIA) that they are in an irrigation district that should be able to comply with SGMA requirements thanks to the nature of the sandy soils and the surface water made available by the Kings River. She explained:

“This summer…we didn’t have to pump any groundwater because of the ample snowpack in the Sierra and the availability of surface water run-off from the snow melt.”

But that doesn’t mean the new regulation doesn’t keep them up at night worrying that the restrictions will become more onerous down the line.

“For us, SGMA is a big issue, of course. It is for anyone who farms in California — the Valley in particular. However, our main concern is not so much if we can become ‘sustainable’ as currently written — we should be able to. It is what happens when California’s regulatory agencies or state legislators move the goalposts, which could very well happen, given this state’s political make-up. Many of us fear that they will (note I didn’t say ‘may’) change the regulations, which could make it even more difficult down the road to become — or to stay — sustainable,” said Liz Hudson.

Water Solutions

While at first glance the situation appears dire for farming, the ag industry is not taking it lying down. First and foremost, counties must become more water independent. Lombardo said:

“Ventura County needs to be less dependent on the California State Water Project, as it is not reliable. Some areas of our state do not even have access to state water.”

In response to the crisis, Lombardo has formed her own company, dubbed Global Water Innovations Inc., which is an industry partner with the National Alliance for Water Innovation (NAWI). They are focused on making the impossible possible by bolstering the available water supply in the county.

“My goal with Global Water and our partnership with NAWI is to create water organically within the basin. Capture and reuse oil produced water, irrigation water run off, brackish water, and contaminated water. For this to work for agriculture, the technology has to be achieved at a price point that works for the crops being produced. This means: well head treatments, zero liquid discharge (no brine), and alternative energy sources. We are conducting pilots now. The goals for this technology are achievable,” said Lombardo.

She isn’t alone.

Sarah Woolf and her brother run a farming operation at the intersection of the Westlands Water District and Fresno Irrigation District. They grow almonds, pistachios, tomatoes, garlic, and onion crops. She also runs a water company that’s aptly named Water Wise, a marketplace of sorts in which she matches farmers possessing excess water with those who need it.

“I help farmers with their water needs – sourcing water, managing water, and working with neighbors on water issues,” she said.

Woolf noted there is a lot more interest in sourcing and securing surface water supply as a result of the groundwater pumping restrictions.

“There’s not enough surface water to meet the farmers’ needs. They’ve been relying on groundwater but now groundwater is limited. There’s a definite shortage and now there’s no fallback, which is what the groundwater was.”

She goes on to explain how in some cases, a farmer can make more money selling water than they can from farming. It’s year-to-year dependent based on the crop markets and water supplies. In a dry year, the water has a higher value.

Woolf believes most farmers have already come to terms with the fact that a percentage of their land will be out of production as a result of SGMA. How they deal with it is a process they’re figuring out now.

“It’s not a permanent fallowing of the ground but often a fallowing of the ground when the market is high so that it’s more profitable,” said Woolf.

SGMA will affect the Woolf’s farm, as they use a fair amount of groundwater. They won’t be able to farm as much land as before the groundwater restrictions were put in place.

In the meantime, Woolf is encouraged by a resilient farming community.

“We’re pretty innovative,” she concluded.

While it all seems complicated, according to Diener, the solution to California’s water problem is simple. “We need more reservoir storage. We must be able to store more surface water. Everybody wins with more surface water. Even environmentalists who want better water quality for fish. If we don’t save it, we can’t use it.”

Diener is encouraged by a new set of biological opinions by the Trump administration that should direct more water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta in Northern California to farmers in Southern California.

“It’s nice to see somebody is finally saying these policies have been a failure for over 10 years. All are suffering – the fish and the farmers. Let’s try to fix it,” said Diener.

*This article originally appeared in GAI sister publication, the Women in Agribusiness Quarterly Journal, Winter 2020, V6i1. Reprinted with permission.

Let GAI News inform your engagement in the agriculture sector.

GAI News provides crucial and timely news and insight to help you stay ahead of critical agricultural trends through free delivery of two weekly newsletters, Ag Investing Weekly and AgTech Intel.