September 20, 2019

By Michael DeSa, AGD Consulting, and Jeremy Stroud, Bonnefield Agricultural Investment

Food is one of mankind’s most basic survival needs and yet, the means by which is it produced is largely misunderstood and underrepresented by the investment community. While agriculture, in particular farmland, is one of the oldest investment sectors in the world, many investors are skeptical of incorporating it into their portfolios because of a lack of clarity as to how it fits into their overall investment strategy, limited liquidity, or from a fear of volatility due to direct commodity exposure. The reality is that the long-term structural trends within this sector are firmly entrenched as key value drivers, offering accessible opportunities to investors willing to explore diversification across the value chain.

Investment Opportunities Abound Across the Asset Class

Within the agricultural value chain, there are a number of different opportunities for both return generation and capital preservation. The upstream segment of the ag value chain includes inputs to agriculture, such as seeds, crop inputs, machinery, technology, and farmland. Three in particular have grabbed investors’ attention: biologicals, precision technology, and farmland. Biologicals are crop input products derived from naturally occurring chemicals and/or living organisms, while precision ag technology consists of a host of technologies designed to make the practice of farming more accurate when it comes to growing crops and raising livestock. These two sectors are generally regarded as a higher risk and therefore demand higher returns – a potentially attractive proposition to an experienced investor looking to exploit early-mover advantages. According to a March 2018 article published by Forbes on the biological sector in agriculture, biologicals have expanded their sales at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 17 percent.1 Investors are often drawn to this sector by compelling profit margins, which can be as high as 20 to 40 percent.2

While there are still challenges with the lack of harmonization across regulatory organizations, market fragmentation, top-level consolidation, and a competitive landscape dominated by large multi-nationals, the sector will remain an important tool in the farmer’s diversified toolbox employed to enhance yields in a sustainable manner.

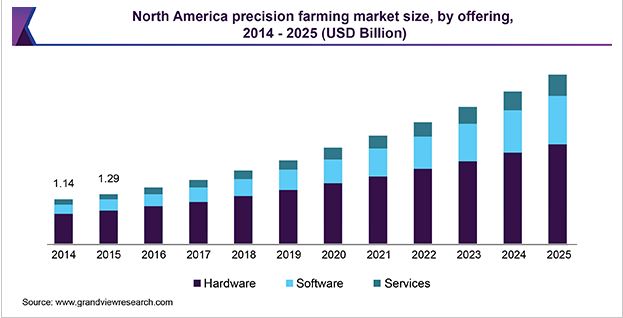

Precision ag technology has been one of the most innovative and disruptive sectors within the asset class. Advances in computer vision, artificial intelligence, and analytical software have fundamentally transformed the operational processes and expectations within the industry. Estimates show that the global precision farming market is expected to reach US$10.23 billion by 2025 with a forecasted CAGR of 14.2 percent during that period,3 highlighting a prolonged interest in this sector.

The pressures of resource scarcity, increasing population, and changing dietary demands will continue to benefit the ag technology sector as young, innovative producers will be expected to produce more food with less water, fewer traditional chemicals, and with less impact on biodiversity.

Production agriculture includes animal protein, fish, and of course, farmland. Farmland has historically proven itself as a long-term, stable store of wealth, appreciating nearly 9 percent annually over the last 70 years in North America.4

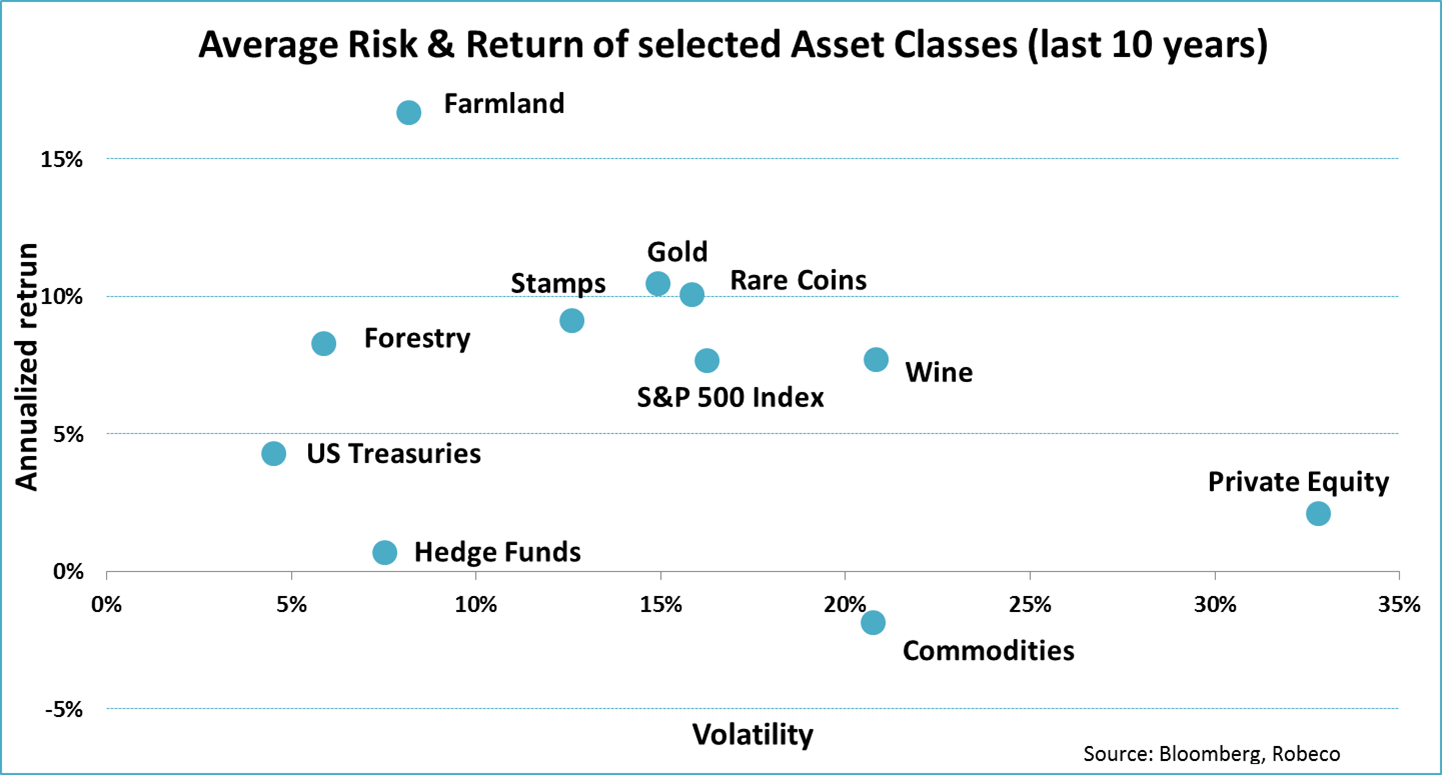

When compared to other selected asset classes within the U.S. markets and global commodities, farmland and forestry have upheld their reputation for years as uncorrelated, low risk asset classes with strong annualized real returns. Additionally, as a “real asset”, farmland will never reach a nominal value of zero so long as it remains productive.

Figure 2 – Historical Volatility vs. Return for Selected Asset Classes, 2008-2017

Source: Morningstar, Macrobond, NCREIF, Hancock Natural Resources Group (1993 – 2017 Sharpe ratio in parenthesis)

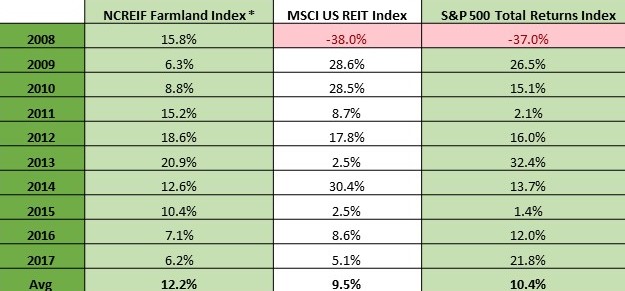

Farmland investments outperformed the S&P over the nearly 10-year span from 2008 to 2017. As the graph below also illustrates, the 2008 financial crisis had virtually no impact on the NCREIF Farmland Index’ investment value, further highlighting agriculture as a secure, stable alternative uncorrelated with the equities market.

Market Index Comparison – Annual Returns 2008 – 2017

| Note: * Consists of 727 U.S. agricultural properties with approximately US$8.5 billion.

Sources: National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF), TIAA/University of Illinois – Center for Farmland Research (Correlation and standard deviation data from 1970 -2016) |

Finally, mid and downstream opportunities within the sector offer additional ways for investors to capitalize on several macroeconomic drivers. Large harvest yields generally lead to lower commodity prices due to market saturation, but for downstream groups such as traders, processors, packagers, retail distributors, and wholesalers, this means their processing plants may operate at a greater capacity, while input materials are reduced in cost. Midstream investments can provide investors with less naked commodity risk and if diversified across crop type and geography, can serve as a hedge against the cyclical nature of the agriculture asset class. Investments in downstream assets can also provide investors reduced exposure to direct commodity risk and additional coverage of other resource sectors, such as alternative power generation, infrastructure, renewables, water management, and even construction.

Investing across the value chain can be synergistic and reduce intermediation and inefficiency costs. Attractive agribusiness opportunities are available across the globe, if you know where to look and what to avoid.

Myths, Misconceptions, and Means of Mitigation

Agriculture can be misunderstood as an asset class. Illiquidity can be seen as an obstacle and value chain components may be taken in isolation, painting an incomplete picture of the risks and rewards. Capital is often misallocated and misaligned given a particular risk tolerance and asset diligence is frequently approached with a “one size fits all” solution.

Illiquidity is often cited as a primary reason for avoiding the agricultural sector. There are, however, creative options in this real asset space. Secondary markets for farmland are becoming a real possibility for private investors as the customer base for ag-focused crowdfunding platforms and parceled ownership structures increase. Lower interest rates have also opened the door on the debt side for increased allocations to ag lenders. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, total non-real estate farm loans were up nearly 8 percent from a year ago. Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT) also offer opportunities for retail investors with higher liquidity options. Gladstone Land Corporation (LAND) is one of two publicly-traded Farm REITS. Finally, many institutional investors are also looking closely at higher-value permanent crops with longer production lifecycles. These long-term agreements offer a strong return over a given time period while simultaneously providing lower price volatility for the off-taker.

Allocation is often an area that new investors find challenging. Some see only the growth projections within the broader sector and interpret lower adoption rates as an indication that an opportunity remains to capitalize on the future growth. In certain trends this may be true (aquaculture, alternative meats, impact investing), but in others the ship has already sailed (current variable rate technologies, farm management software, and GPS guidance). The precision agtech market has been so saturated in Noerth America for so long – with many of the products not living up to company claims – that fewer farmers are adopting certain technologies. Couple this with depressed commodity prices, and you’ve created an environment where many farmers find themselves with just enough free cash to incorporate only the technology absolutely necessary to make it through a growing season.

Asset and portfolio managers must understand the risk profile an investor is willing to assume. As an example, in order to minimize the associated with an ag investment into an Emerging Market (EM), investors need to first parse emerging market risk at a country-level, then isolate specific, often localized risks that may not be readily apparent at the country-level assessment phase. Some of the greatest risks revolve around politics, macroeconomics, and rule of law. While there is little that can be done to manage political and macroeconomic risks, investors need to fully assess these environments, understand all possible scenarios, and make the right tradeoff for themselves between potential risks and rewards.

Finally, it is paramount for investors to understand the relationship between differing components of the ag value chain as these present opportunities for de-risking and diversification. Upstream assets are positively correlated to prices, so if the price of corn rises for example, farm incomes go up and farmers are more likely to spend money on technologies, inputs, and expansion. However, as you go downstream, the relationship to price often becomes inverse with value added processors taking more direct commodity risk than retail distributors. Processors have significant fixed assets, so they tend to do their best when harvests are abundant, which often leads to lower prices. Strong harvests mean they can run at higher capacity, but at a detriment to the farmer, who likely sold that commodity to an off-taker at a lower price. It is imperative for investors to understand the interrelationships within the value chain, common misconceptions about the asset class, and how to mitigate identified risks.

How to Get Started

Over the past 10 years, individual investors, family offices, private equity, pension funds, and even international sovereign wealth funds have begun to realize the value proposition inherent in agriculture. Advances in logistics, storage, processing, technology and management practices have each played a role in opening this asset class up to investors of all types.

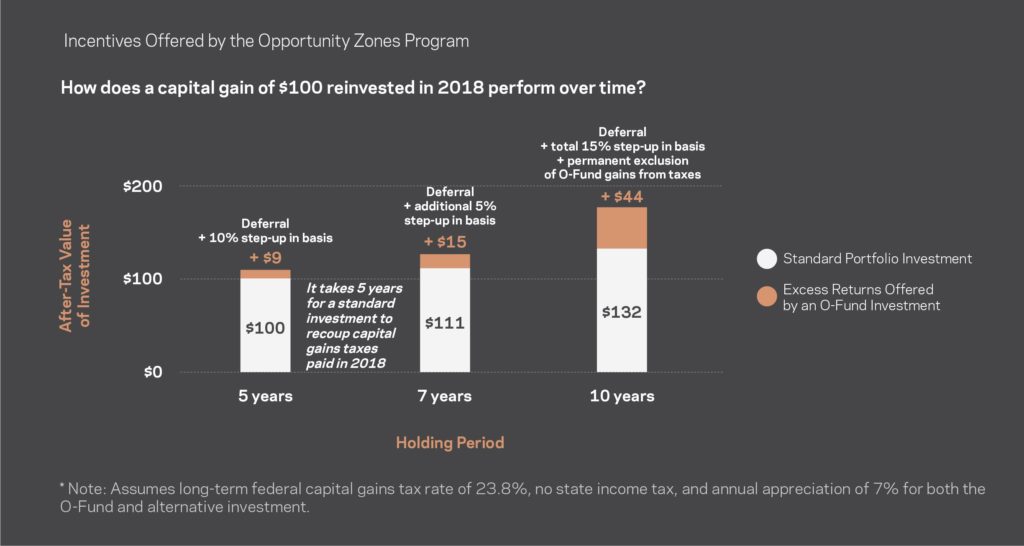

There are a range of investment structures at varying entry price points and scale available to both retail and institutional investors. At the private/retail level, the May 2017 Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (JOBS Act) established crowdfunding provisions that allow early-stage businesses to offer and sell securities. This Act helped spawn a host of ag-focused crowdfunding and syndication platforms such as Harvest Returns, FarmTogether, FarmFundr, and Farmland Partners allowing retail investors and family offices to participate in larger ag projects at lower-cost entry points. The recent establishment of “opportunity zones” in the United States as well, targeting economically distressed communities where new investments may be eligible for preferential tax treatments, have also helped foster the creation of ag-specific opportunity zone funds for individual and institutional investors alike.

Often, the simplest and most direct way to gain exposure to agricultural farmland is to either own/operate the land yourself, own the farmland but outsource the management, or purchase farmland, then lease it back to an operator. According to the 2016 Preqin Special Report on Agriculture, 90 percent of investors in agriculture/farmland are open to land-owner focused opportunities. If a first-time farmland investor prefers to own/operate the land directly, it is advisable to do so onsite and in partnership with a management company for the first few years until the owner becomes comfortable with all the components of running the operation. If an investor wants direct farmland exposure, but not operational risk, there are structures available where individual investors can own titled parcels of farmland that aggregate to form large plantations with economies of scale, thereby achieving operational efficiencies and cost savings without the logistical burden falling directly to the owner. Sale/lease-back models can also be attractive to private and certain institutional investors, so long as there are clear rights of tenure and land use agreements between the landowner and leasee. These can be more challenging if the landowner is an absentee owner, and while lease agreements typically do not incentive the leasee to care for or develop the farmland long term, it can be an attractive way for an investor to earn near-passive income from a farmland investment.

Private Equity (PE) is largely new to the agribusiness sector, but over the last 15 years, there has been a steady rise of PE groups taking positions within the global food and agriculture space. From 2005 to 2014, more than 200 new investment funds began operating in the food and ag sector, accounting for approximately US$44 billion in assets under management.5 According to Prequin’s Special Report on Agriculture from September 2016, several of the world’s largest private equity firms, including Paine & Partners, Proterra, Altima, AMERRA, and Blue Road Capital raised a total of $6 billion across 11 funds.6 Since the basis of PE is direct investment into a company, a large initial capital outlay is required, which is why this segment tends to be dominated by larger funds. It is paramount, however, that a new-to-ag PE fund tailors their return profiles, timelines, and risk tolerances to align with those of the selected sub-sector and geographic regions. For example, a California-based permanent crop operation is likely not well aligned with a PE firm who wants geographic diversification, 20-plus percent net IRRs, and an exit timeline of five to seven years. That being said, a PE group looking to achieve 20-30 percent net IRRs with an exit in five to seven years and a developmental focus could be well matched with a soybean crushing expansion project in Brazil.

Investing in productive farmland at an institutional scale, particularly from pension funds with longer time horizons, has been historically difficult due to asset fragmentation, low turnover, and a high degree of differentiation between various commodity types. Oftentimes, more patient capital providers prefer to acquire large, contiguous farms with steady cash flows. As these farms are typically offered through a competitive bidding process, this naturally drives up acquisition prices, compressing return projections and cap rates. Therefore, some funds are seeking groups that have access to a continuous stream of proprietary, off-market deals which offer low acquisition prices.

Conclusions

Whatever the investment thesis, geographic preference, return profile, risk tolerance, or investor type, the ag value chain has the spectrum of opportunity to offer something for everyone. The uncorrelated nature of the asset class, its tangibility, preservation of wealth possibilities, and return profiles in emerging markets offer a natural inflation hedge and diversification to the traditional paper markets. The inevitabilities of a growing middle class and the population at large, including changing demands for higher quality foods, entrenched consumer concerns with sustainability and traceability, and the continued competition for key resources are all unmistakable value drivers that underpin the agricultural sector as a resilient and viable asset class.

Primary Author – Michael DeSa is founder and managing director of AGD Consulting, a U.S.-based, strategic advisory and business development firm servicing the agricultural and resource sectors in emerging and OECD markets. His agricultural engineering background, 10-years of project management experience with the U.S. Marine Corps, and agribusiness investment experience make him uniquely qualified to counsel companies on investments in agriculture.

Primary Author – Michael DeSa is founder and managing director of AGD Consulting, a U.S.-based, strategic advisory and business development firm servicing the agricultural and resource sectors in emerging and OECD markets. His agricultural engineering background, 10-years of project management experience with the U.S. Marine Corps, and agribusiness investment experience make him uniquely qualified to counsel companies on investments in agriculture.

Contributing Author – Jeremy Stoud is an agricultural investment analyst with Bonnefield based in Toronto, Canada. With a background in international food business, he offers insights on global agri-food and water investments, value chain analysis, and economic systems. He has volunteered and worked with a spectrum of primary and vertically integrated agricultural groups in North and South America, Europe, and Africa.

Contributing Author – Jeremy Stoud is an agricultural investment analyst with Bonnefield based in Toronto, Canada. With a background in international food business, he offers insights on global agri-food and water investments, value chain analysis, and economic systems. He has volunteered and worked with a spectrum of primary and vertically integrated agricultural groups in North and South America, Europe, and Africa.

SOURCES

[1] Savage, Steven. “Updates on the Rapidly Growing Biologicals Sector in Agriculture.” Forbes. 18 March 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevensavage/2018/03/15/update-on-the-rapidly-growing-biologicals-sector-in-agriculture/#50b1865c55be [2] Transparency Market Research. “Global Biologics Market Will be Worth US$479, 752 Million by 2024; Global Industry Analysis, Size, Share, Growth, Trends, and Forecast 2016 – 2024. 06 October 2016. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-biologics-market-will-be-worth-us479-752-million-by-2024-global-industry-analysis-size-share-growth-trends-and-forecast-2016—2024-tmr-596150181.html [3] Grand View Research. “Precision Farming Market Worth $10.23 Billion by 2025 | CAGR 14.2%.” May 2019. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/global-precision-farming-market [4] https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/land-use-land-value-tenure/farmland-value/ [5] Valoral Advisors. “The Rise of Food and Agriculture Private Equity Space.” September 2014 Report. https://www.valoral.com/wp-content/uploads/The-Rise-of-the-Food-Agriculture-Private-Equity-Space-September-2014.pdf [6] Preqin. “Preqin Special Report: Agriculture.” September 2016. Accessed 30 May 2019. https://docs.preqin.com/reports/Preqin-Special-Report-Agriculture-September-2016.pdf

Let GAI News inform your engagement in the agriculture sector.

GAI News provides crucial and timely news and insight to help you stay ahead of critical agricultural trends through free delivery of two weekly newsletters, Ag Investing Weekly and AgTech Intel.